Recently at a camp a swimmer asked about the differences between Total Immersion Swimming and this or that other program, noting, “they seem about the same to me!”

Of course, I wouldn’t totally agree with that statement, that TI and Program X or Program Y are generally the same. Though I am sure the coaches in these programs all desire the same marvelous results for their swimmers, Total Immersion’s understanding of how to get there seems to diverge at critical points (from my outside perspective on those programs). But rather then taking up time to dissect and compare and debate, instead I offer a grid we can use to objectively examin the advice that would be offered by any other program giving swimming advice.

With this framework in mind a swimmer may have a way to evaluate whether that advice has thoroughly solved the problems we face as human swimmers.

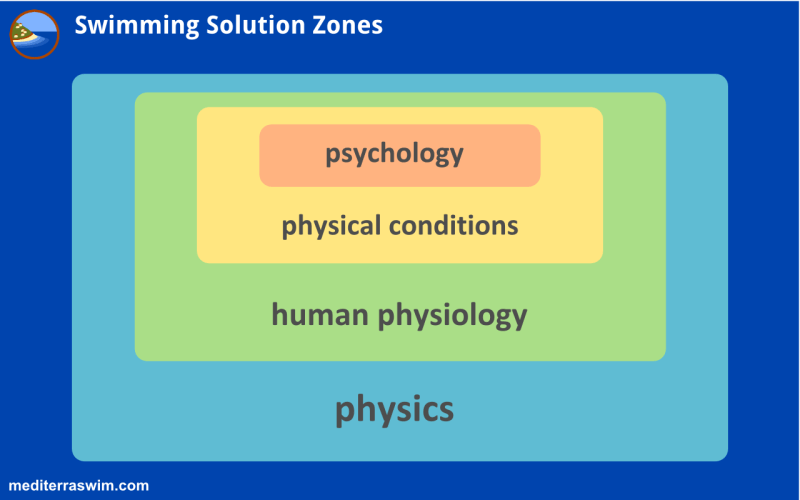

I propose dividing up the examination into four zones, in order along a critical path:

- Physics

- Universal Human Physiology

- Personal Physical Conditions

- Psychological Conditions

In swimming we have these problems to solve:

- how we can easily learn to swim

- how we can swim easily

- how we can swim farther and/or faster

- how we can enjoy swimming and training

Physics is the starting point of all discussions about swimming because these laws determine what can be done, what cannot be done and how much it will cost in terms of energy. Learning to swim, swimming easily, swimming farther and faster, and enjoying swimming all must first pass through the physics of the situation.

#1 – Physics

The stroke correction must first address the physics of the swimming problem.

Physics is totally impersonal. It does not care what color you are, what age you are, male or female, young or old, what emotional hang ups you’ve developed over the years, how cool your tattoo is, or what personality or body type you have. It is impartial. It does not grant favors and it does not negotiate. Every human athlete, however exceptional in genetics or talent, must first obey the laws of physics.

And, in practical physics the solutions to problems that we come up with are expected to be convergent. There may be many creative hypothesis for how to get the job done, but from scientific experience we now generally expect rigorous testing to lead to a single superior (and as scientists like to say, ‘elegant’) solution. The physics of motion and thermodynamics channel us toward a single superior solution to a movement-and-energy problem like swimming. We might see a revolution in how to move the human body from time to time, but what results, even from a revolution, is a jump over to a new and superior model – these revolutions do not broaden the market, but narrow it down by revealing the inferiority of the formerly-held ideas.

Consider the refinements in the front crawl stroke over the centuries, and some of the major revolutionary steps that led to the modern crawl: put the head down in the water, alternately revolve the arms, flutter kick. It is humorous to note that, in London in 1844, even though the Native American swimmers, using their native form of a crawl stroke, soundly spanked their British breast-stroking competitors – those British nobles were too proud to learn from the example and put their heads underwater in order to swim faster! It is a lesson to watch out for the pride in tradition, because tradition is meant to be corrected from time to time.

Note that we have now four valid competitive stroke branches: freestyle, backstroke, breaststroke, and butterfly. They are divided into four separate branches because the stroke styles are NOT EQUAL in terms of speed and efficiency. It is easily understood when you try them and we take those difference for granted. Many human swimmers, for whatever reason, gravitate toward one and specialize in it, and we readily accept that too. But we don’t compare the performance between those stroke because the stroke styles are not equal. Furthermore, technically, in ‘Freestyle’ one is permitted to use any of those stroke styles (hence, the word ‘free+style), yet everyone chooses front crawl because it is indisputably the best for going the fastest, farther for least energy. Enough testing has been done by humans to conclude this with no further debate… perhaps until a new stroke revolution comes along!

Looking at other objects that require extreme efficiency and speed – note the trend in how jet planes and attack submarines are designed. Over the years their shape has evolved toward a single distinct, superior design. These industries have a intense pressure to be fast and efficient and therefore their rigorous testing for speed efficiency has consistently pointed to a convergent solution in fluid-dynamic situations… the same fluid situation we have in swimming.

In other words, I am speculating that the variations we see in the fastest crawl stroke swimmers in the world will diminish, and we will be left with more subtle nuanced differences as the speed-and-efficiency pressures of world records force these solutions.A hundred years ago we would have seen a wide range of (now humorous) styles, which are clearly inefficient to our modern sensibilities. To the eyes of those back then, the styles of our modern competitors would all look nearly the same. But a hundred years from now, I can easily imagine those swimmers will be using a style refined to a much deeper degree, and all the swimmers will be using it. The subtle differences in those strokes would not be obvious to our primitive eyes.

This is my prediction – physics will force the stroke toward such a single, distinct technical solution to the swimming speed problem.

And why would physics force a distinct superior stroke style for humans?

#2 – Universal Human Physiology

Before we look at what makes humans unique and different from another, we need to look a what makes all humans the same. This solution must first address universal physiological realities before adapting to individual advantages and limitations. This is what we are referring to when we talk about practicing and mastering the fundamentals of the sport before working on the individual tricks to get an edge. Work on proper movement patterns that apply to all humans moving through water before looking for a short-cut with one’s unique physiological features.

I have this popular anatomy book on my shelf next to me in my office. Ever notice that they don’t make different anatomy books for different ‘body types’? Nope. Just one set of physiological principles all humans must abide by.

Human physiology shows us how the various systems in the body work together in all humans. The human structure has distinct ranges of movement for each section, and movement patterns that can be safely and powerfully supported. When humans keep movement within this range and use proper movement patterns, they are the safest, the most powerful and can be sustained longest. Any deviation from this range and pattern introduce greater risk of premature wear and injury. This is the serious concern we have about all the stroke variations we see promoted in a swimming.

For some quick examples, here are three major areas of conflicting advice in swimming crawl stroke:

- the position of the head (looking forward versus looking down)

- the shape and path of the recovery arm (varieties of shape and trajectory)

- the shape, timing, and path of the underwater stroke (the ‘catch/hold’ in TI terminology or ‘pull/push’ in traditional terminology)

Yes, there are a variety of ways each of these body parts and movements can be arranged within the normal mobility range for humans. But arguably only one of those pathways is truly safest and strongest and get the most done for the least amount of effort, while the rest have some compromises in safety, power and/or efficiency.

For example, there is a variety of ways the arm/shoulder can be swung around on the recovery, but there is one pattern that is the safest and requires the least amount of energy. All are possible, but one is superior. The others introduce some compromise in safety, power and/or efficiency and therefore increase risk of injury.

All four stroke styles (crawl, backstroke, butterfly, breaststroke) use the same shoulder design but each applies different loading and moves along a different pathway. Each stroke style has its common shoulder pains and some strokes are clearly more injurious than others. The strokes are not equal in their safety, their power, or their efficiency in regards to the shoulder health. So, following that logic, how can we assume a variety of crawl stroke styles are all equally good and safe and effective? There is just no physiological logic to support it – there are many variations we see in the crawl stroke among swimmers at all levels but they are NOT EQUAL.

Do ‘whatever feels good to you’ or ‘what fits your personality’, whatever you’ve been using for the last 10 or 20 years as a child champion is not a sound way to judge the safest, most powerful, most efficient movement pattern for a human. You can’t feel the risks you are taking now when the consequences of joint destruction are experienced years later. Since swimming is not an activity the human land-mammal was designed for, one should get some solid input on healthy joint mobility patterns before committing to a certain variation in the stroke. Unfortunately, most of us first learned our style under the (supposed) guidance of a traditional swim coach who taught us to do what everyone has been doing since he/she was a competitor, and used the same justifications (or no solid physiological explanation) for why we do it that way. Hence, the statistics for swimming injury remain scandalously high.

Quick happy story: a few months ago at a series of workshops we held in Moscow I had a former competitive swimmer and now fitness club swim instructor in one of those workshops. She had been suffering from neck/back pain for years while swimming, had been to many coaches and doctors seeking relief, but found none. In a few minutes I showed her how to release the head, put it into proper spine alignment by looking straight down (stop looking forward), which removed the local extension fault in her cervical spine and removed the subsequent chain reaction of tension down the spine, and 20 years of swimming pain went away immediately. Needless to say she was ecstatic with joy and relief – and swimming easier and faster because of it. Previously, no one had given her permission to move her head out of the traditional but faulty forward-looking position. Yes, looking down is strange because it is not the way we were taught and not the way we’ve practiced, but it is the correct (= safe and strong) position for the head according to physiology, and it conveniently happens to be the most hydrodynamic head position too.

The human body has developed as a land mammal working upright under gravity, and is designed to handle loads and movements in this orientation. It seems to be universally understood among physio professionals that the human body is indeed meant to bear loads and perform a wide range of difficult tasks, but does so in the safest and most powerful way under a relatively narrow set of patterns for proper movement. The human body is meant to be heavily loaded and to move under that load, but do so without causing damage only if loaded in certain ways and moved in certain ways. Deviate from that path and the body defaults to secondary or tertiary support solutions which seem to ‘work OK’ for a while… until they don’t work any more. Deviation from best movement pattern, even if they do not initially cause pain, dramatically increases the risk of premature wear and injury for the athlete. (Thank You Dr Kelly Starrett for making this crystal clear in your presentations and texts.)

With that said, let’s now consider the individual swimmer’s unique working conditions…

And, we’ll talk about that in the Part 2.

© 2015 – 2016, Mediterra International, LLC. All rights reserved. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Mediterra International, LLC and Mediterraswim.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

This resonates in a coincidental way! I am a struggling older TI newbie, but gradually all the non-intuitive facts of swimming have made sense to me and the TI adaptations to these facts have become natural to me. I am now comfortable in the water, although I am not fast. I finished my first Half Ironman in great shape. I have another one coming up in late July and I would like to be a little faster. So in true TI style I have been going back to the drawing board and repeating short sets of as perfect technique as I can manage.

My preferred pool has just closed for a 2 year renovation project, and in casting around for a replacement pool today, I stumbled on another city branch pool that happened to be open, next to an athletic track that I was doing mile intervals on this morning. I wandered in to this new pool, and discovered it would be suitable to be my new substitute pool. In chatting with the desk lady, I found out that at that very moment they were having a public “conditioning swim” session, and she urged me to drop in and have a try. She even lent me a pair of extra swim trunks that they had in the lost and found, so I didn’t have much of an excuse. I went in and found what I guess must be typical swim racing technique training being run by a coach who herself had been a competitive swimmer.

I was really clumsy, having only learned TI freestyle, so I fumbled through the breast stroke and back stroke (both of which I faked amazingly well) and skipped the ‘fly parts. However what was interesting were the drills. There was one freestyle drill where you take one stroke and do six kicks (I had to revert back to my pre-TI 6-beat kick style, which was not too confusing) then the other arm stroke and six kicks etc. It was something like alternating side TI skate drills, and in fact I found it was actually easier, as I have never been able to get the roll-on-your-back-to-breathe without distorting the axis or straight laser line out of my head. Because we were doing it somewhat faster than how I normally do skate, I was able to keep the momentum up better and breathe without lurching and without any extra effort at all.

Except, of course, I was doing it TI style, with lead hand planing downward and face 90 degrees down. So she “corrected” me, with the lead hand at water level, and the head higher “brow cutting the water like the prow of a boat” as she put it, explaining that the sharp front of the head provided less resistance than the blunt top of the head full in the water!! 2 years ago I might have taken her at her word, but now I have a more nuanced view of the secondary balance effects of a seemingly trivial change in head position. I was too polite to argue, especially seeing as how I was the guest student. Besides, I was kinda carried away at how fast I was going, with all the peer pressure driving me to exert harder than with my usual solo TI drill efforts. I hope I didn’t deteriorate other TI efficiencies apart from the above head position one.

So obviously I disagree with certain factual dogmatic points she made. However, there are certain advantages of this arrangement, if I choose to attend the “swim conditioning” sessions regularly. The camaraderie is comfortable, and I am motivated to keep on exerting more, which is harder to do alone. I know the usual TI advice is to work on technique, which is what I do best alone. But there is no one to push me to go harder when I tire, and hopefully, this is where I learn to maintain god technique when I tire. After all, she can’t and won’t stop me from utilising other TI insight, stroke timing, recovery and catch technique; I can switch in and out of brow at waterline style whenever I want. I think the insight into the difference is valuable, as long as I can tell the difference, and as long as I am cognisant of the danger of non-TI “creep” into my technique, which I will continue to practise in solo sessions.

Or, to put it into your framework, although the physics is “wrong” or at least not in keeping with my mind-frame, the psychology, that is the encouragement and group activity works for me, as long as I keep a firm grip on the hard-won TI instinct.

Does this seem like a reasonable approach?

Hi Su-Chong Lim (first, you must teach me how to address you – your first name is _________ ? I am aware that family name is used first in some language/cultures)

Let’s see what your own answer to the question might be after reading Part 2 to this.

I would like to praise your inclusive, open-hearted attitude to participate with an open mind and body, while maintaining your own critical thinking about the activities. And you could participate in it, even when things are not idea or ‘correct’ in your understanding. That takes a secure heart and mind. It is worth experimenting and giving this coach the chance to show you her ideas and allow experience to influence your judgment. If only she would likewise be open to testing her ideas against others, to experience a different approach and consider the possibility that there is a better way. But you were invited as a student not as a teacher so it is proper to submit to the training voluntarily, not argue with her at points of disagreement, and walk away with your own thoughts about it unless she asked for feedback.

Since few clubs may have strong coaching in all 4 zones one might be inclined to accepting inferior physics/physiology in order to have the strength of a group to train with. That is fine, but only if people were aware of the weaknesses in that coaching program and could compensate for it by getting supplemental input elsewhere (and not have that program coach resist that outside influence).

And, you have touched an important social factor too – many people prefer a group atmosphere and this is very motivating and encouraging. Though there are tens of thousands of TI practitioners in the world and 400+ certified coaches, they are not evenly distributed around the world. So, not easy to find a kindred club to join.

Yes, Matt, you are absolutely right, most East Asian cultures (Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Vietnamese, for example place the Family Name first. What is confusing is that often, for the sake of alignment with western naming systems, many individuals reverse the traditional order. This is often done in Western media reporting too, and also, gradually, the English language media in some of the original countries are starting to make the switch too. I have done this for my name as I moved from Singapore, where I had grown up in a Chinese family, to Canada forty years ago.

To add a further layer of confusion, it is also traditionally common in Asian societies for individuals to be known to their friends, even fairly intimate ones, by their family names, and even if the family names are extremely common, as mine is. So I might be known as “Old Lim” in distinction to another (younger) Lim.

So my surname, or family name is Lim (I have found that referring to it as my last name can be ambiguous!). My personal name is Su-Chong; and I would be pleased to have you call me that.

Incidentally, you may remember me as the total body sinker in previous correspondence. I am happy to report that with your encouragement and some practice, I have learned to live with the body density I have, and more to the point, to swim with it. I just completed my first Half Ironman 2 weeks ago, helped a lot by a wet suit, and it went, well, swimmingly.