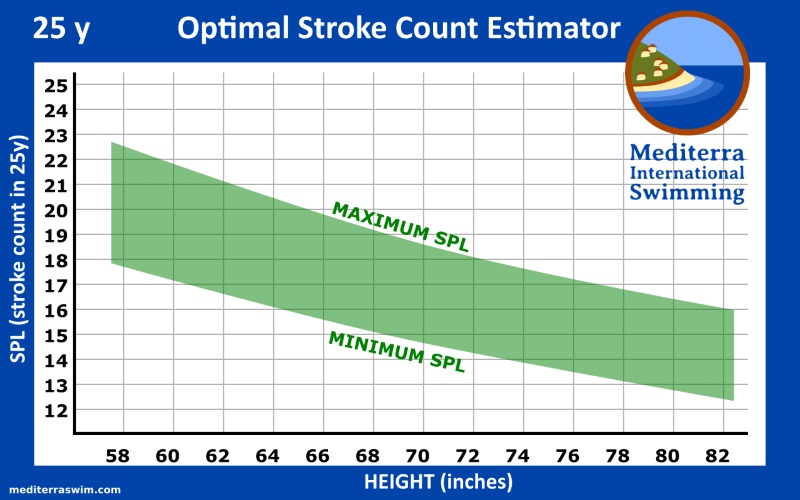

These charts will help you estimate your optimal Stroke Count, or in technical terms, your Strokes-Per-Length (SPL) range. These charts are just to help you aim in the right direction. There are many factors you should consider when fine tuning which range of stroke counts are best for your body and event. Read When Choosing Your Optimal Stroke Count for more insight, and you might enjoy reading The Back Story Of The Stroke Count Charts to learn about how they were created.

25 Meter Pool

This chart is for SPL in a 25 meter pool, assuming you take a 5 meter from push-off to first stroke.

25 Yard Pool

This chart is for SPL in a 25 yard pool, assuming you take a 5 yards from push-off to first stroke.

50 Meter Pool

This chart is for SPL in a 50 meter pool, assuming you take a 5 meter from push-off to first stroke.

Terminology

In Mediterra’s style of practices, when we refer to SPL, we will use a variable like “SPL N”, or “N-1”, or “N+1”, etc.

N = the lowest number in your appropriate SPL Range. It’s not the lowest SPL you can possibly achieve, but the lowest within the range of appropriate SPL for your continuous swimming – in that range that is good for your energy use and shoulder health.

If you have an SPL Range of 16 to 19, then your SPL N = 16, N+1 = 17, N+2 = 18, N-1 = 15, etc.

How These Curves Are Calculated

Based on a great deal of observation and comparison of data we see a strong case for setting a swimmer’s SPL range between 55% and 70% of their wingspan. The minimum SPL on this chart corresponds to 55% of height and the maximum corresponds to 70%.

We chose to use height for these charts because most people know immediately what their height is, and for estimation purposes, that is close enough.Wingspan is the measurement of your arms spread wide, measured from finger tip to finger tip. Wingspan provides the more accurate estimate of what your stroke length potential is. In humans height is approximately the same as wingspan, within +/- 5% margin of difference. We see this difference between height and wingspan also matters but we’ll save that discussion for another article.

Precise Personal Metrics

So if you want to do the math to get more precise, personalized SPL for yourself you need this data:

- Your wingspan or height (W)

- Your pool length (PL)

- The distance of your glide (pushoff) to stroke #1 (DG)

Then we start the calculations working with Stroke Length (SL).

Calculate your minimum 55% SL:

- W x .55 = min SL

Calculate your maximum 70% SL:

- W x .70 = max SL

Then we convert to SPL which is dependent on your pool length and glide:

Calculate your minimum SPL:

- (PL – DG) / max SL = min SPL

Calculate your maximum SPL:

- (PL – DG) / min SL = max SPL

Push-Off Matters

Some things to keep in mind as you use Stroke Counting…

How far you glide after pushing off from the wall to your first stroke affects your stroke count. If you followed the math calculations above you’ll notice that a short push-off will require you to take an extra stroke or two to reach the far wall, while a long one will allow you to take one or two strokes less.

Work on keeping this push-off and glide distance consistent on every lap. If you have a long glide (5-6 meters) you can aim for a lower end of your SPL range. If you have a shorter glide (3-4 meters) you can aim for the higher end of your SPL range. 4-5 meter push-off to glide is a good average to aim for.

Narrow Your Range

This chart estimates a range of about 5 SPL counts. However, through testing and practice we recommend that you narrow your personal range down to 3 SPL counts.

For example, for a male swimmer about 40 years old, 180 cm tall, the chart above suggests a 16-20 SPL in a 25 meter pool. If he has highly developed streamline and stroke efficiency he may aim for 16-18 SPL as his target SPL range. If less developed he may aim for 18-20 SPL.

What Is Your SPL Range Used For?

They function a bit like multiple gears on your bicycle, allowing you to adjust the pressure and frequency to use energy just the way you need to for a particular event or conditions.

Your higher SPL count is generally for shorter distance, higher tempo, or lighter pressure strokes.

Your lower SPL count is generally for longer distances, lower tempo, or higher (steady) pressure strokes.

***

© 2019 – 2020, Mediterra International, LLC. All rights reserved. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Mediterra International, LLC and Mediterraswim.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Hi Mat,

How would you adjust for age and build (thin person with skinny arms/paddles)? I imagine that a person with arms with more surface area would be able to hold water better than one with “stick arms”?

Thanks.

Lin

I was just preparing the second post to publish minutes later when you asked the question first!

https://mediterraswim.com/2019/06/04/when-choosing-optimal-stroke-count/

Arm size affects the amount of resistance one can build, which then depends on how much muscle strength (and technique to manage it) is available to push against that resistance. This ties into the age/power topic.

Mat: I am an adult onset TI swimmer (sorta swam, splashed around in the pool prior to that) since turning 64 in 2012. I am now improving very slowly if at all after the first few years of more rapid progress. I am 162 cm tall and about the same wingspan, so my green zone in a 25 m pool is supposedly 17.5 to 22.5 strokes. If I really take my time I can easily get 20 strokes or even 19+ for one lap. But I think that’s cheating. If I go at 1.30 seconds a stroke on my TT it is difficult for me to sustain 22-23 spl for more than 2 or 3 lengths.

For clarity, mentally call the first beep on push-off as “0” I hit the water with my first spear on the “2” beep and call that beep my new “0”count. So I’m not getting much of a glide (I’m not gliding longer to get less SPL so as keep my criteria consistent).

I am very lean and tend to float very low in the water, so I need to rotate more than other people to get a breath and despite that pronounced rotation I suspect I lift my head a little. Is this just an alibi with no sustainable foundation; in other words do I just need to get more focussed to get better technique?

Hello Su-Chong Lim,

Let’s step back a bit. At this point, why do you feel you need to achieve longer strokes? Just because the chart says so, or because you have a pace goal, or an efficiency goal that requires it? This is where those considerations in the following post When Choosing Your Optimal Stroke Count can be helpful. If you have a really short push off until that first stroke then you need to add 1 or 2 to that stroke count range.

The amount of power, the amount of torque you are applying affects how far you travel too – a wonderfully streamline sea kayak doesn’t slide very far when a weak paddle is applied to the water. Power has to be proportional to the mass of the vessel. I can’t evaluate your power, but at 71 years old, one might not have as much power to apply on each stroke, and no matter how streamline the body is, it will not travel very far on each stroke except at an unreasonably slow tempo (which allows too much deceleration).

You could, and at some point should, work on the other side of the question. You can use the comfortable SPL N you have now and begin challenging yourself to hold that SPL while gradually increasing tempo (over weeks). This will increase your strength from a different direction. First, pick a test distance to swim to measure your capabilities by – a 200 or 400 or 800 swim. Set your TT to 1.35 and then see what SPL you can hold consistently for most of or for the entire test swim, then call that ‘N’ SPL. Let’s say you start with being able to handle up to 900m (in 50, 75, and 100 intervals, if you like) with N = 21 SPL at 1.35 sec tempo, then spend a week or two working on holding 21 SPL with 1.32 sec tempo. When you feel your body adapting to that work load (= it feels easier to do, less failure) then spend another week or two working on holding 21 SPL with 1.29 sec tempo, and so on. Then go back to your test swim and see if you can hold N-1 SPL for that entire swim or a, with tempo at 1.35.

In summary, when you’ve done all you know how to do to refine balance and streamline at easy or no tempo constraint, start challenging your body with a slightly more difficult tempo and let this, over a few weeks, build more strength. Then you may find that you can swim with longer strokes more easily, because you built both more strength, and your brain (without you focusing on it) refined its streamline and balance skills further under those more stressful conditions.

No specific speed or distance goal — just that I seem stuck at that one tempo /spl/ distance combination, and despite being reasonably fit and not bad upper body strength (or so I thought), seem stuck at higher end of green zone range rather than towards middle of range. But given your stroke count protocol, perhaps I’m actually further into the green zone than I thought. Will work on your recommendations. Much obliged.

Especially when you don’t have a particular speed goal, another important measure of optimal stroke length is what feels good, or what produces a pleasing effect while swimming. If your stroke feels particularly short or your don’t seem to slide as easily as you think you should, then that could motivate you to work on making it longer, or rather, work on what may likely be causing drag. The length is a product of lowering drag and/or increasing power – the length is just one way to measure those. So rather than focus on the length as a goal, you might just work on being sensitive to any part of the body that seems to be provoking excessive drag and work on smoothing that out. The lengthening of the stroke becomes a symptom of improvement, rather than the goal.

And, we need variety in our training stimulus. Spend time working at different tempos like 1.40/1.35/1.30 and different SPL N, N+1, N-1, and take skills and make them work on short with uncomfortably fast strokes, and at distances that are a little fatiguing. Building your capabilities for a wider range of speed, intensity, distance will support your progress of a very specific direction (like just being able to swim with a longer stroke).

You might just be where your body needs your SPL to be. The variety in training will help make that even easier.

Sir, I’m eighteen years old and am 176 cm in height and my wigspan is almost 190 cm, and have a long torso. Is my body type suited for short distance sprints or long, and what should be kept in mind to be better than the rest competitors in both cases. Thank you

Hi Pranjal. In general a high wingspan-to-height ratio is an advantage for any swimmer, in any event. Yet, there has always been a statistical curve where certain kinds of bodies are favored, but there are still high performing exceptions. I can’t tell if you would be in the curve or an exception. The higher up one is on the ladder of elite competition the more that certain kinds of bodies will be favored in a particular event. Lower on that ladder and the factors that contribute to success (at that lower level) are a lot more convoluted. Without knowing anything about your background in swimming and what your current condition and performance is, I would not want to limit you by suggesting your body shape is suited more for this event or that event, and discourage you from working on the other. But if we were to start a discussion on this, then your wingspan and wingspan-to-height ratio would be only one of the pieces of information that we would want to look at to get an idea of what you and your body might be suited for. Your strength matters. Your motor response speed matters. Your technical skill matters. Your mindset and personality matter too because different events require a different approach – and we would need to see how well you could adapt your characteristics to the event. We would want to see how you are performing in long events and short events – in terms of tempo and stroke count, from length to length on the entire race – to give us some indication of your current strengths and weaknesses. If we saw that your were already tapping into the advantages of your body dimensions in one event then this may encourage you to explore that direction more. But you might also have instinct for how to use your body well in both kinds of events.

How does weight factor into drag and speed? Also what stroke is the chart intended for please? It consistently takes me an additional two to three strokes per 25m versus backstroke. Either way the chart will come in very useful and it’s a confidence booster knowing that my stroke appears more efficient than I thought it was. I’m a 190cm woman, finally my height is good for something 😂 I guess I need to figure out how to pick up the pace without breaking down the technique which tends to be the case.

Great questions, Anna. I see that in posting the charts we’ve assumed something that is not obvious – these Stroke Count Charts are for freestyle, and each stroke style would have a different stroke count chart. I’ve only done the count survey on freestyle, though the concept of using stroke count would work the same for any of them. You can take your own stroke count for the other strokes in a few practices to establish a baseline, and then explore the ways you can modify your stroke patterns in each to reduce that stroke count and evaluate under what circumstances you’d want to do that.

If you are laying your body down on the ‘water mattress’ completely, horizontal to the surface, letting it cruise along in the neutral zone between gravity pushing down and water pressure pushing up, then your body is actually weightless – however, it still has mass, which means the mass of molecules of water in front of you have to be moved out of the way so that your equal mass of molecules can occupy that space. The swimmer with more mass has to move more water out of the way than one with less mass. However, the swimmer with more mass made up of swim-supporting muscle can move their mass forward more easily than one with the same mass or less mass and less swim-supporting muscle making up that mass. A more buoyant body composition means one can ride a bit higher in the water and perhaps stay parallel to the surface more easily, but they have less muscle to fat ration and thus less power available to move that mass along. There’s more to discuss around buoyant bodies riding higher and enduring more wave drag at the surface, but let’s stick to mass. The fastest swimmers in the world tend to be fairly tall and more muscular than the average swimmer – we might guess that the sport selects those on route to produce the best mass and power balance.

Practicing with discipline to maintain best technique under stress, under fatigue, is the only way to develop truly efficient speed. Those who do not might get faster, but it is an expensive form of speed, and the inefficiencies they train into their nervous system ultimately limit how far they can go. Practic with patience and persistence in maintaining precision under incrementally increasing difficult swimming conditions…

Hello, I am 40 years old female, 169cm and 64kg. I have been swimming as a kid but not competitive, more for technique and endurance. After a two decade break I started swimming again. My spl is where it should be according to your chart 17-19 but it feels very slow. I create a drag I can’t identify and therefore fix. Also don’t really slide but I do rotate. I guess I am not buoyant and hips are easily dropping. It feels easier with swim buoy but still slow. After about 3km swim 5 times a week for 2 months with various drills for all 4 strokes I would expect to see improvement in speed but I don’t. Any suggestions on what I should pay attention to? What would really help me increase the speed ? Thank you,

Hi Masha. There are a lot of opinions out there for ‘how to get faster’ and it would be very difficult to give a truly useful answer in a few paragraphs. There are a few dimensions of development that need attention in any swimmer – there is training the externally visible parts of the body to be in certain positions and move in certain ways and then there are the internal, unseen parts of the body that need to be trained to connect and coordinate smoothly throughout the stroke choreography. Making through the body are a part of the neural fitness you need to develop. Building strength around those connections is then the next developmental focus. Then building metabolic strength, and then mental strength… But that is all just a theoretical framework I would use to examine where your personal needs are. If you do have a lower body that is angling down a bit, this is not a buoyancy issue, its an internal connection issue. There is more to learn about how to connect the lower body to the upper body through internal control of your posture and tying the body from head to ankle into a unified frame so that the whole body works and flows together as one unit through the whole stroke choreography – this is not something we see taught often and when a pool buoy is prescribed then that is a sure sign it is not understood because buoys break the frame (by creating a vertical force applied right where there should be a horizontal force through conenctive tissues) and make it nearly impossible to tie the lower body to the upper body in a meaningful way. A swimmer who finds a buoy more comfortable likely has poor connection through their body while one who has good connection will find a buoy interfering with that connection.

But even when you have the best form – wonderfully streamlined so that making your target stroke count feel easy – you may still be slow because you have to develop strength around that very good form in order to move the body that same distance per stroke in less time. That is what power does. Power needs to be developed by stimulating (stressing) the muscles (and consequently, the metabolism) to work harder than they have become accustomed to. You engage in a cycle of stress-and-rest, within a training set, within a training session and within a training week. For you, since you are doing 5x 3K per week you may need to focus on inserting particular kinds of challenge in your 5x 3K workouts rather than adding any more volume. More swimming of the same kind of training isn’t going to make a difference – changing the quality of your training is.

For this it may be good to pick a specific event you want to use to test and measure your improvement with. Focus on prepareing your body for that event rather than being un-focused with drills and a random arrangement of different stroke swimming. Then you can do training activities that identify and emphasize development of particular parts of your frame and stroke that are uncoordinated and/or weak. Then you can do training sets throughout the week that are designed to build the kind of power appropriate to the event you are preparing for.

This is where having a coach on board to help you prepare for that specific event can help. You can learn a lot about the process of training by having a season of being guided by a coach who can introduce you to it.