Do you know what your optimal stroke count is or should be?

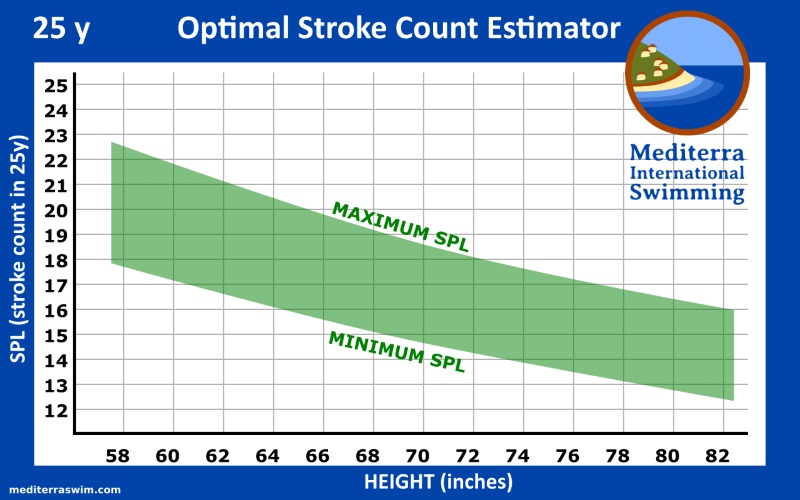

You may have seen similar ‘Green Zone’ charts used or posted in various places in TI discussions (and you can see them here on our blog and you might enjoy reading The Back Story Of The Stroke Count Charts to learn about how they were created). I originally designed these charts and provided a version of them to TI for common use. It is fun to see them become a popular reference. But I need to stress that these charts provide an ESTIMATE of what stroke count may be more efficient for your body, not a rule.

As the one who developed the evidence-based calculations behind these particular charts, I am aware of the considerations and assumptions that went into how the green zones were defined. When looking at this chart for yourself, please realize that there are many factors that can and should affect the expectations you set for your stroke count. You may fit nicely into that green zone or not.

First, these charts are based on data and observations of the performance of people who have been swimming with decent technique and who have had swimming-specific fitness in place for many years. These do not necessarily reflect only those who are swimming fast, but but they do reflect what we expect to see from those who have reached a high level of neuromuscular refinement in their stroke skills.

Don’t despair if you are a fairly new or older swimmers. There are factors that may affect your ultimate stroke count goal, but you have far more potential for long, smooth strokes than you may realize. Read on…

Push-Off Matters

One of the first points everyone using the Optimal Stroke Count charts needs to immediately factor into their stroke count is how far you push off the wall to your first stroke (the moment where you start the count at “1”). The stroke counts on these charts are based on the distance you actually take strokes after push off, not the whole length of the pool. These charts all assume a 5 yard or meter mark for your first count.

If you have an extraordinarily long push off, like to 6 meters, then you need to lower your SPL range by 1. If you have a short push off, like to 4 meters or 3 (which is common for those who do not have skills turns and streamlined glides) then you need to add 1 or 2 strokes to your SPL range.

This note has always been included on my slide presentations and discussions of SPL, but I haven’t seen that posted with with TI version of these charts, so it is important for me to emphasize this point.

Age Matters

We may say that stroke length is a product of:

- your ability to streamline

- your ability to transfer available power smoothly, effectively

- your ability to generate more power

Fortunately, the first two are neural and you can keep improving these as you get older and older, compensating for some amount of lower strength.

We all know that strength potential is diminishing with age. But here are two things to counter that…

- I may confidently guess that you have much more strength potential than you are experiencing right now

- You are likely not doing what you can to increase strength

In other words, you have limits, but you are not coming close to those yet. Even though you may be showing signs of getting weaker, it is because you are not doing more to preserve strength and increase it. So, I say this with the utmost kindness, but don’t give me those “I’m getting old” comments yet!

Fitness History Matters

When you look at the stroke length causes above, you notice that your neural and muscular fitness matters.

Those who have been swimming (with decent stroke technique) for decades are going to have neural and muscular fitness greatly conditioned for swimming movements. This is going to make it much easier for them to make small adjustments and slip into more suitable stroke count range, if they are not there already.

Those who have been swimming (with decent technique) for just a few years or less still have some years of swimming to go to provoke deeper adaptations.

But I cannot guess how each person will respond to the stroke length training stimulus. Some have a movement history and skill level that allows for relatively short learning process while others need much more time. Your swimming-related fitness and complex athletic movement history matters.

However, it is greatly beneficial to your health and longevity to persistently work on it despite your movement history. So, don’t let your recent arrival to swimming or exercise be an excuse. You need to get moving and the more your activity causes you to learn, the better!

Sex Matters

In society, we have very interesting discussions going on about sex, gender, and identity, especially in relation to athletics. While I am so pleased and challenged by the positive changes taking place in society to be more inclusive, the fact remains that physics does not care about our gender and identity. It is definitely shown in science that hormones and sex-related biological difference affect strength potential, and hence the reason we have segregated the biological sexes in competition.

How we relate to the humans around us, and how we relate to ourselves in our own mind is one worthwhile discussion. But what resources this biological body has available for moving forward in the water is quite a different discussion.

Simply put, biological males tend to have a hormone situation that enables them to have more strength and biological females tend to have far less. And women’s strength potential in some forms tends to diminish more quickly with age than men’s (though there might be arguments against that).

But looking back at those three stroke length causes, only #3, strength potential, is affected by these biological differences. The first two are neural, and as far as I know, biological females are at no disadvantage there. So, that may be a reason to keep a single version of these charts in place for all kinds of people.

Wingspan Matters

You may have noticed that different sports tend to attract different body shapes. In swimming, long arms and long torsos seem to be favored.

The human wingspan (spread arms wide and measure from fingertip to fingertip) tends to be approximately the same as height. But there is some variation, with humans showing at least 5% range on either side, with longer or shorter arms. This is (either affectionately or derogatorily) referred to at the ‘ape index’, since apes display obviously long arms compared to their height.

Your Wingspan / Your Height = Wingspan Coefficient (WC)

The marvelous Coach Suzanne Atkinson labeled this the Wingspan Coefficient many years ago when we were working together to develop these concepts.

If your WC is more than 1.02 then you may aim for a lower stroke count range because your long arms provide you with a mechanical (leverage) advantage. If your WC is less than 0.98 then you may aim for a higher stroke count range.

Injury History Matters

I hear that when you damage tendons and ligaments, they never quite heal back to 100% normal. There may be some change in the shape, which may result in a change in the space of the joint, and thus a negative change in movement patterns. With a tear there is often nerve damage in the tissue which changes the proprioception and lowers precise control of movement in that joint. There are therapy approaches to help the athlete develop protective compensations, but likely very few injured athletes are getting this kind of attention and instruction to retrain the joint and fully compensate. Because of this some of us have ended up with joints that are more vulnerable to injury when we are not extremely careful.

So, we need to carefully approach longer strokes with good shoulder mechanics and monitor the signals our joints send us about how that joint is being affected by the stresses longer or faster strokes impose. Almost always, even with the most solid joints, the stroke pattern is shifting slightly when trying to apply more power, so this is where extreme attention to upholding precise patterns is important in every set that imposes greater loads on the joints.

Careful training may reveal signals from the body that, despite holding superior form, the joint senses a risk of injury when working with a stroke longer than a certain length, so we should note that limitation. It may be possible to get some therapy and do some strength training on that joint to reduce or remove that limitation.

The Event Matters

Speed is a product of Stroke Length x Stroke Rate. As the speed increases the body is increasingly challenged to hold steady both SL and SR. Higher speeds make the swimmer want to shorten the stroke and speed up the rate to compensate, but faster spinning arms tire out more quickly too. The system is stressed and as that stress increases with speed, the swimmer will have to give up one, the other or a bit of both. But the well-developed swimmer is trained to handle that stress at higher speeds and then give up only a calculated amount of SL and/or SR.

This is why, in sprint events, the stroke length is shorter and the stroke rate is faster, and conversely, why in middle and longer distance events the stroke length is longer and the stroke rate is slower. But, statistically, the better swimmers at both ends, tend to have more steady and generally longer stroke lengths than their less successful competitors. It tends to be the longer stroke length that wins races, but optimally long, not excessively.

So, if you are training to compete in short sprint distance, you should expect your stroke length range to be a bit shorter and faster than when you are training to compete in longer distance.

If you are training for leisure distance swimming, then you need to test out stroke length x stroke rate combination to see which allows you the smoothest velocity (not too much acceleration and deceleration on each stroke) so that you can conserve momentum. But that is another discussion…

Adaptation Matters

Even once you get some stroke count goal in mind, realize that adaptation takes time. Your body has developed proximate efficiency at whatever pattern it is already familiar with, even if it is far away from the stroke pattern that would be more universal efficient for your body. Initially, when the body needs to learn a new movement pattern, it can take over 6 weeks (think like 6 or more weeks and 18 or more stroke length stimulating practices in that time span) for neural adaptations to take place, to the point where the change feels permanent and preferred.

So, when you are working on shifting your stroke count, you need to work on this over weeks and months, not just try it in a few practices.

***

© 2019, Mediterra International, LLC. All rights reserved. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Mediterra International, LLC and Mediterraswim.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

You must be logged in to post a comment.